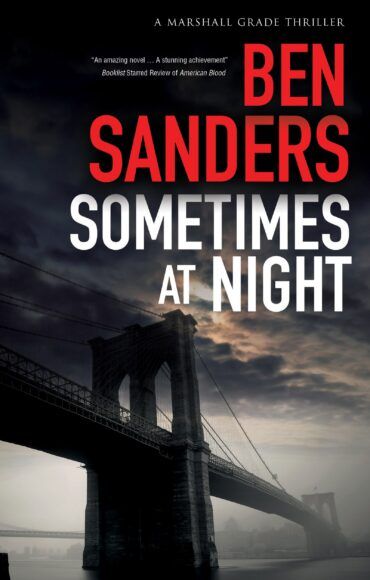

Why Read Crime?: Ben Sanders on his new novel Sometimes At Night

by Ben Sanders on 5 August 2021

For lovers of Jack Reacher and Jason Bourne there is a new gun in town – a noble loner called Marshall Grade

Michael Robotham, NYT-bestselling author

When a former NYPD colleague is shot dead in front of him, undercover cop turned private investigator Marshall Grade discovers there’s far more to the killing than meets the eye.

Here, author of the Marshall Grade thrillers Ben Sanders reveals the truth about why he writes crime, and explores the popularity of the genre.

In one form or another, the questions I’m asked most often about my writing are, Why the fascination with crime? And why the fascination with darkness, evil, misfortune? The answer is that I’m not particularly interested in any of those things. Or rather, the reason those ideas or elements feature in my books is because they are actually tools with an ulterior purpose: they generate suspense.

Suspense is a state of the reader’s mind, manifesting as a subconscious question: what is going to happen next? The goal for the writer is to continue to prompt that question, and more important, to make the reader care about the answer. As far as I’m concerned, suspense in its most potent form is generated when engaging characters face danger. Not just blind and indiscriminate bad luck, but danger with consciousness, and steady, grim intent directed at someone in particular. Danger of the human variety.

It’s often implied that people read crime or mystery out of pitch-black curiosity, or schadenfreude. No doubt some people do. But what most readers look for in the genre, despite the often-grueling content, is a feeling of optimism: mystery solved, adversaries and adversities overcome—at least to some extent. It’s a rare beast of a book that worsens inexorably, and ends with utter abjection for all involved. We want a narrative arc that lends cogency to the formlessness of actual experience, and terminates in a more-or-less clean fashion: a pleasing defiance of reality, where meaningful closure is rare.

Engaging characters facing mortal peril, and a story with a solution. They’re vague parameters that could fit an infinite number of stories, and yet they’re still useful: like a magical map for storytelling that won’t show you where to go, but which can be referred back to later, to check you’re headed in the right direction. And they’re parameters that helped me shape my main character, because I needed someone who could face danger of the human variety, and overcome it.

I’ve read crime and mystery novels since I was fourteen. I loved Robert Crais, Robert B. Parker, Lee Child. Authors with stories of people fixing mortal problems. As a young reader, uncertain of where I might be heading, I found their heroes particularly appealing: guys who were dead sure of themselves, and had carved out a niche of supreme competence in a bad world. Guys who could be relied on for a solution, and were constrained only by their own convictions. They were entertainment and an inspiration, and I wanted my anti-hero Marshall—an ex-undercover New York cop—to follow something of the ethos that those characters represented.

Marshall is a man who’s been betrayed by a system, but his experience has given him the skills, enemies and quirks that make him pretty useful at the helm of a crime novel. I’ve used him in my books three times now, and he’s never let me down. I always want to know what he’s going to do next.

I hope you like him, and I hope you enjoy Sometimes at Night.